29 Ottobre 2009

English

The new St. Stephen’s Square (Piazza Santo Stefano) 1990-1991

Luigi Caccia Dominioni and Daniele Vincenti*

The widening in the Via Santo Stefano is one of the oldest parts of the city of Bologna. The medieval cross-roads, originally dating back to the late period of the Roman Empire, creates a funnel-shaped space between Via Santa Gerusalemme and Via Santo Stefano, delimited by the symmetrical façades of the monumental buildings along the two diverging sides, and at the back by the religious complex known as the “Seven Churches” dating from between the 8th and 9th centuries.

Luigi Caccia Dominioni’s instinct told him that this area, created by the widening of the two roads, was the perfect place for a piazza, and Dino Gavina transformed this intuition into facts, submitting the idea of a modified paving project to the city council. The perfect opportunity to implement such a plan arose when the council decided to relay the various underground technological infrastructures (cabling, piping etc.), and gradually the project took shape, after careful research had been carried out by Bologna’s City Centre and Monumental Buildings Department, headed by the architect Roberto Scannavini: this research provided the architects with detailed knowledge of the historical evolution of the site (further archaeological finds, indeed, confirming the pertinence of the project).1

The proposed plan was to restore the original shape of the site, re-establish the centrality of the piazza opening out towards St. Stephen’s Church by means of a concave form of paving, recoup the unitary nature of this specific area by levelling out the road network, thus creating the impression almost of a cavea (a horseshoe-shaped auditorium).

The complexity of the site is what generates the tensions that animate the space in various directions: Caccia Dominioni managed to identify these tensions and integrate them into a design that in some way evokes the original signs of the city. The city space is thus animated by the presence of these references, concealed for years but now highlighted by the new design of this urban space; the new perspectives generated by the reopening of the cavea-shaped piazza create a symbiosis between the porticoes of the surrounding buildings and the streets that pass through. In a central position, the façade of the “seven churches” regains its primary role and a solid base (denied it up until this point, after the work carried out in 1934 had sunk the sacristy into a kind of basin, cutting off the perspective and modifying its proportions).

The architectural centre of gravity of the site is undeniably the façade of the Seven Churches complex: this renders the new piazza a sacred place, a fascinating sacristy of this “mysterious” religious complex. However, the sacristy was once also a market place, that is, a trading place, a truly profane space and thus a cross-roads, a stage for the enacting of the everyday lives of the local inhabitants.

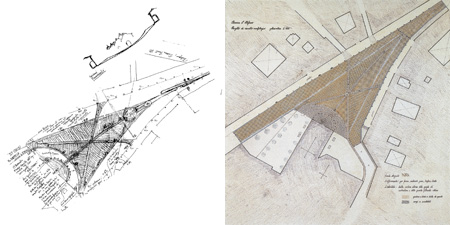

In his architectural sketches, Luigi Caccia Dominioni traces a series of fluid objectives: the granite “guide lines” bend and merge, flush, into the pavements beneath the porticoes; the depression of the cavea rises up, with no steps, to be paved in porphyry or in Pesaro stone, and a green marble centre, a paved “cameo” almost, emerges slightly from the ground and marks the confluence of the streets. When it came to implementing this design, for certain specific historical-morphological reasons, cobblestone was chosen in place of porphyry, and a few steps were included to facilitate movement in the steepest sections of the cavea.

[photogallery]dominioni_album[/photogallery]

The colour scheme of the new concave piazza was defined by the use of two different kinds of stone: amber-red cobblestones from the Trentino region were used for the larger areas, while light-grey granite slabs from Sardinia were employed for the lenticular sacristy and for the “guide lines” marking the pedestrian crossing points and framing St. Stephen’s complex. The two paved strips running parallel to the porticoes were created using alabaster-grey cobblestones from the streams of the Apuan Alps.

Alessandro Vicari

Note

* The re-edited essay has been taken out from the volume by Alfonso Acocella, Stone architecture. Ancient and modern constructive skills, Milano, Skira-Lucense, 2006, pp. 624.

1 The project was co-ordinated by Bologna’s City Centre and Monumental Buildings Department.