13 Dicembre 2010

English

The construction of walls. Tectonics/stereotomy*

Cape Masullo featuring Casa Malaparte, Capri

The chapter on Stone Walls that opens this work is one of the most important as it introduces the reader to the wide-ranging and variegated subject of Stone Architecture dating back to the very earliest of times. The thread we have attempted to weave between contemporary architectural design and an often extremely remote architectural past, serves to support what we consider to be a fundamentally important, albeit simple, belief concerning the permanence of walled architecture: our basic hypothesis is that we can only get a true grasp of modern stone architecture if we already have a thorough understanding of the varied architectural experiences from the past.

The examples of ancient stone architecture brought to the reader’s attention, the suggested similarities between distant examples (in both temporal and geographical terms) which nevertheless appear almost inexplicably related, in our view represent not so much an erudite curiosity as a means with which to explain the relationship between those “things” that are of fundamental importance to the development of a certain sensitivity towards, and of a deeper understanding of, the construction of stone walls both past and present. To put it briefly, we believe that stone architecture is inextricably rooted in ancient “times” and “crafts”.

Thus the true aim of our study is to reconstruct the original sources and archetypes of this architecture, not so much through any “official” reading of these archetypes, but rather through an investigation of the deeper underlying concepts. Stone walls, beginning from their earliest constructional design, are proposed as one of the founding concepts of architecture; their long-lasting character and eternal presence simply amplify the scope of our present analysis.

Architecture is fundamentally determined by the nature of the construction materials and methods employed: while architecture has been historically characterised by a considerable variety of such materials, especially in modern times, the range of construction methods has been rather more limited. When the attempt is made to exploit the mechanical properties of those objects that exist in the natural state, the types of possible structure tend to be extremely limited: the relatively few resulting categories of structure do, however, allow for a significant degree of internal variation and interpretation of the chosen construction type and its respective architectural features, if not its static functioning.

The historical process designed to transform the often inhospitable natural environment into a sheltered microcosm (and then gradually into a place with specific functional, aesthetic and symbolic characteristics) took place in primitive architecture through the adoption of two fundamentally important, and to a certain degree, diametrically opposite constructional archetypes: one was the thin, lightweight, linear wooden frame “jointed” together and held taut; the other was the walled structure, made of earth, clay or stone – a massive structure prevalently subjected to compression. The former building technique may be said to be a traditionally northern system, while the latter is more characteristic of Mediterranean civilisation, which from the remotest of times developed a conception of architecture based on the hardness, mass and indestructibility of stone, which in Kenneth Frampton’s words “has left its mark of the world for eternity”.1

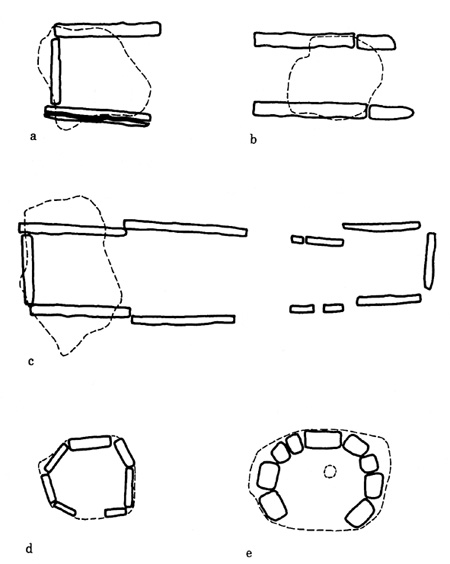

Plans of dolmen in Apulia: (a) the “Paladines’ Table”; (b) Bisceglie; (c) Cisternino; (d) Placa; (e) Scusi

The primitive cultures of the Mediterranean area already made use of enormous stones for the purposes of what we shall call “megalithic construction”, where the said stone, albeit preserving its natural, original form, was in some way subject to a process of transformation, of adaptation to a given purpose. These very earliest uses of stone – for example in the construction of ancient menhir, of cyclopean walls and of tholos (circular chamber-type) tombs – are a clear expression of the solidity, the permanence and the hardness of the rocks and mountains that “encircle” the Mediterranean, which the French writer Fernand Braudel illustrates so brilliantly in his “Mediterranean Memoirs”:

From the very beginning of time, millions of years ago, at a chronological distance beyond the imagination, a large underwater chain (the geologists’ Thetis) extending from the Caribbean to the Pacific, cut in two – in a parallel sense – what was to become, much later, the mass of the Ancient World. The present Mediterranean is the residual mass of Thetis’ waters, which date back almost to the beginning of the earth.

It was at the expense of this extremely ancient Mediterranean – that once extended well beyond the current sea – that the repeated, violent uplifting of the Earth’s crust during the Tertiary period took place. All the mountains from the Cordilleran region to the Rift mountains, the Alps, the Apennines, the Balkan Mountains, the Taurus Mountains and the Caucasus Mountains, emerged from this ancient sea. They have eroded its space, they have exploited the sediments deposited in the immense hollow of the sea, its sands, clays, sandstones and limestones – often prodigiously thick – together with its deeper, even more primitive rocks. The mountains that enclose, suffocate, barricade and sub-divide the long coastline, are the flesh and bones of the ancestral Thetis (…) The Mediterranean area has been gobbled up by these mountains, which have extended to the seashores, uninvited, amassed one against the other, the invariable framework and background of every landscape. 2

The Giants’ Tomb at Arzachena

Besides constituting the geographical and visual horizon of the Mediterranean, the mountains and their rocks represent a vital resource for Man: they provided the first materials for the monumental architectural structures of the primitive megalithic period linked to the advancements made at that time in the working of copper and bronze. The entire Mediterranean area was to be influenced by this phenomenon, one that was to partially transform the landscape with the erection of large-scale monoliths – the vertically-erected menhir, the parallel walls covered with horizontal slabs called dolmen – varieties of which were also to be found near more northern seas (as in the case of the Breton cromlech, or of the gigantic stone circles of which Stonehenge near Salisbury in England is the most impressive example). Further examples of this primitive representative and symbolic employment of stone include collective stone tombs, the most fascinating of which feature false cupolas with overlapping stone slabs laid one over the other right to the top of the construction.

For some time now there has been heated debate over which of these archetypal constructions lies at the “roots” of architecture as such. In fact, the origins of the subject have been variously identified with the primitive “tree” dwelling (the mythical “House of Adam” in Paradise), then with natural rock caves, which the tholos tombs seem to be directly based upon. However, others, such as Vittorio Gregotti, on the basis of the previously-submitted idea of Choisy, perceives the roots of architecture as lying in the symbolic, monumental menhirs:

Before transforming a support into a column, a roof into a tympanum, and before laying one stone on top of another, Man had already laid a stone on the ground in order to mark a site within an unknown universe: in order to take account of, and modify, that universe. Like all forms of ascertainment, this required both radical movements and an apparent simplicity. 3

The Giants’ Tomb at Arzachena

The great megaliths already possessed some of the characteristics that were to become a constant of stone architecture: the solemn “positioning” of the stone, its intrinsic hardness making it resistant to wear and tear; the resting on, and supporting of, other elements thanks to stone’s inherent solidity and stability; the massive form of the building materials positioned so as to gravitate towards the ground and “take root” therein. This constituted a new, artificially-contrived world based on the use of an abundant natural material.

While in the case of the menhir, the stones themselves created an “open” structure within a natural context, the dolmen represented a more “inclusive” spatiality produced by massive walls composed of stone blocks: in this case, the megalithic structure pre-empted the mature technique of stereotomy (from steros, solid, and tomia, cut), which led to the creation of continuous structures consisting of the sum of various layers of stone, more or less regular, and consistently massive and “enclosing”.

On the other hand, Northern Europe – an area with a wealth of forests – saw the greater development of the concept of the tectonic (from the Greek tekton, builder) indicating a direct reference to carpentry. As Kenneth Frampton fully explains in his work Studies in Tectonic Culture, the structural process of creating the wooden framework whereby light, linear elements (created using the wood from tree trunks) are assembled to give an open structure positioned at certain points on the ground, to be subsequently “enclosed” by curtain walls.

This very different building concept, as shall be illustrated in the chapter on Columns, was to directly influence the very same Mediterranean stone architecture, leading to the evolution of the Greek temple whereby stone, gradually introduced to replace wood, was to be shaped, arranged and organised, in terms of planimetric and volumetric composition, in such a way as to reinterpret the shape of the primitive wooden framework of religious structures during the geometric period.

Note

* The re-edited essay has been taken out from the volume by Alfonso Acocella, Stone architecture. Ancient and modern constructive skills, Milano, Skira-Lucense, 2006, pp. 624.

1 Kenneth Frampton, “Reflections on the scope of the tectonic”, in Studies in tectonic culture, John Cava (ed.), Cambridge [Mass.]: MIT Press, 1995), p. 430.

2 Fernand Braudel, “Seeing the sea” p.19, in Memory and the Mediterranean, (New York: Vintage Books 2002) (first published as Les Mémoires de la Méditerranée, 1988), p. 365.

3 Vittorio Gregotti, “Speech at New York Architectural League” (1982). The quote can be found on p. 8 of Frampton, Tectonic Culture.