18 Aprile 2013

English

Digital technologies and creative talent

[photogallery]tulle_album[/photogallery]

A contemporary designer must know how to make good use of the protean possibilities that modern-day avant-garde industrial tools offer. Today mechanical tools are not merely static, but can learn from experience, or rather are ‘trained’ to react to specific feedback. The unvaried repetition of an action or a function, a synonym of mechanicity, can be overcome when a human being guides the productive process and identifies input for improvement.

The innovative frontier in the modern-day stone industry is to produce artefacts that man cannot make by hand. These are serial elements in their aesthetic and mechanical qualities, but have been obtained by working with a natural material. At the base of this research into precise, constant results, are the substantial changes that have occurred in both the fields of production and design.

In contemporary stone design, before the form materialises it begins with automatic computer design, a magical tool that instantaneously – one could think – creates or produces ideas, pre-representations and models of any artefact. Software creates precision technical design and generates realistic images of the object on the computer screen. It then transfers geometrical and dimensional information to manufacturing programmes in order to produce the artefacts.

With CAD (Computer Aided Design), design is closely linked to production through the CAM (Computer Aided Manufacturing system). In what way and to what extent can a computer really ‘aid’ a human in these tasks? Of course the machine supports the designer, allowing the production of precise technical design and providing information for tools in the production and manufacture of an artefact, but it is man’s conceptual faculty that guides the action of both the computer and the mechanics of production.

We can see this attitude in the concept, prototype creation and production of the design stone collections created over the years with tenacity and creativity by Raffaello Galiotto and Lithos Design.

Towards the end of the 20th century we saw a special kind of revolution that began in industrial contexts and penetrated the structures of design and training. In the design field – whether it is product design, interior design or architectural design – computerised systems of design, rendering and creating prototypes have become increasingly commonplace, offering a growing potential for pre-representation.

The world of digital design has revolutionised the way we think about design and, like all great transformations, it also has some elements of risk. The danger is to the relationship between man’s creative intelligence and his corresponding productive ability, which is now transferred from his hands to mechanical tools. In the words of Richard Sennett, it is a threat to the development of the craftsman’s ability.1

The formal and material opportunities offered by automatic design, three-dimensional modelling and ‘rendering’ (i.e. simulating real vision) appear vast and ‘spectacular’. We only need to put a few dots on the screen and press a few keys on the keyboard to create a pre-representational effect, made up of two or three-dimensional lines, with great ease. The design can then be modified extremely rapidly and cancelled just as quickly, with fewer consequences than when the design is on paper.

Mutations, regenerations, close-ups and faraway perspectives, created in an instant and infinitely self-generating, are at the designer’s fingertips. And there is a great hypnotic fascination in the interplay of lines and vectorial surfaces in the light, immaterial and virtual world of the computer screen.

It is different, however, when invention and ideas come into contact with real, physical, heavy material. And if the material is stone, the impact is even more striking.

Digital design tools have led to an increasing separation from the creative and manual ability of the author, because of the speed at which an idea can be completed before it is actually produced. The visual simulation possible on a screen is considered highly realistic, independent of the tangible realisation of what is represented.

If these opportunities are undoubtedly a stimulus to creating forms that were undreamt of before, the pre-representational conception made possible by computerised systems may, however, result in the risk of a lack of reflection and in-depth thought on the quality and value of objects.

Representation set down on paper by hand in the past was slow and reflective and forced the designer to think and root the effect of his choices in his mind. Drawing signs, repeating lines with millimetric precision, manually correcting errors, choosing colours and symbols from a limited range of possibilities was very different from testing pre-prepared and virtually endless libraries of weaves, textures, colours and material backgrounds.

Today’s designer works with this abundance of possible options, combined with the speed of automatic design, which compresses reflective and creative moments and he runs the risk of being ‘aided’ by machines instead of directing them and ‘bending’ them towards his design. There are no solutions in pre-set default functions; solutions can only be devised combining a knowledge of material with an understanding of the consequences that can result from different machine settings, guiding the tool to precisely correspond with the pre-set idea.

All Raffaello Galiotto’s work with Lithos Design seems, by contrast, to control this system of representation. The designer’s command of his tools is evident. He knows how to subordinate them and is not dominated by them. By identifying his own language and applying his choices, Galiotto turns the process on its head and becomes the central figure that governs, dialogues, ‘aids’ and directs the machines.

In particular, the work carried out in stone has been made possible as a result of the know-how of this young brand from Vicenza.

The company is extremely dynamic, active and able to exploit the value of its technological resources to achieve the aims of the design, while respecting productive and economic constraints. With an approach that still looks to high quality craftsmanship, Lithos Design knows how to combine thought and action, returning in continual progress to review the design through the tools arranged to create it, and remaining open to the continual circular metamorphosis of the design. Its advantage is an in-depth knowledge of stone, transferred precisely to the designer to obtain a result of organic and harmonious symbiosis.

The risk of imbalance between the pre-representation of the design through digital simulation and the physical corporeity of the product is overcome by the physical knowledge of the reality of the material that the designer is working with, in this case with the specific qualities of stone.

The design and management team – the designer and Alberto and Claudio Bevilacqua, owners of Lithos Design – have directly experienced the effect of light on material, they have discovered the material nature of different types of stone through touch, they know how it reacts to heat, wind, structural effects and to the strong and incisive action of machines on stone blocks.

It is only starting from these conditions that digital simulation is not an imperfect surrogate for reality, but a useful tool for verifying and testing. When one has an intimate knowledge of the properties of stone and the conditions and real constraints that it can pose, his intelligence and creativity in design do not use computer simulation as a tool to remove or dissimulate the real difficulties of the project.

[photogallery]foulard_album[/photogallery]

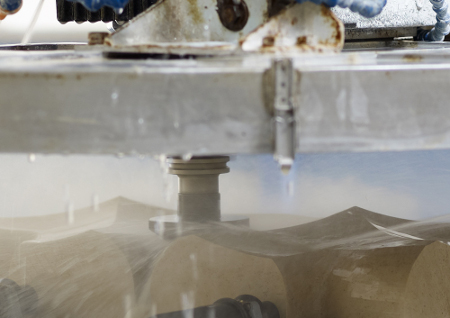

In an ongoing dialogue, the process developed by Lithos Design first configures and checks the design, then the information to be transmitted to the powerful, numerically controlled machines, finally the difficulties that this meeting between tools and the material inevitably generates – to create a model using the millimetric precision of CAD/CAM systems.

Raffaello Galiotto’s work for Lithos Design is designed exclusively to be produced on a machine, in univocal and homogeneous series that encounter the naturally heterogeneous nature of various types of stone. The results – series of artefacts of absolute morphological precision – are achieved by checking and correcting imperfections: a meeting between machine and material and the freedom to adapt natural stone and mechanical components. It is the indeterminate nature and special features of stone, precision moulded by tools, which produce and determine the beauty of the artefacts. Only in this way does stone design acquire ‘character’.

The manipulation of objects generated and developed on computer screens (and, apparently, already fully formed) does not mean that the designer should not revise and re-formulate a design. He should look at it critically, through self-reflection, and reintroduce elements of variability and new developments. Only in this way can research continue to advance and learn and human creativity remain an active, rather than a passive consumer of tools.

Raffaello Galiotto’s method of designing returns to the design in a circular manner, to checks during production, to manual gestures and to the study of proportions in terms of the eye and the human body, which computer design, with its endless scalability, does not allow.

The great challenge met by the artefacts produced along his creative path with Lithos Design, is to continue to be conceived with high quality craftsmanship, with a proper use of digital technology and a real knowledge and experience of material.

The designer, for whom thought and practice are still intimately linked attitudes, aims to resolve the conflict between his visionary nature and manual skill and machines.

With commitment, dedication and constancy in identifying and solving problems, he leaves the design open each time, in a borderline area ready to welcome the next metamorphosis of stone.

Note

1 Richard Sennet, L’uomo artigiano, Milano, Feltrinelli, 2008, pp. 318 (ed. or The Craftsman, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2008).